By Siha Hoque

Dementia is an umbrella term describing neurological conditions and the loss of cognitive function as a result of damage to nerve cells and their connections in the brain. It primarily affects thinking, skills, memory and logical reasoning skills; causing symptoms like personality changes, forgetfulness, a lack of social awareness, language processing and planning. Anyone can develop dementia. Almost a million people in the UK alone suffer from this disease and the debilitating impact it has on their lives, and the lives of those around them. Due to its unpredictable nature and unclear causes, it was claimed to be a disease impossible to cure. In recent years, with research, it appears that there have been some breakthroughs indicating that drugs could be used to reduce the effects of this disease.

There are several main causes to the symptoms we recognise as dementia, including: frontotemporal dementia, where the front of the brain shrinks; dementia with Lewy bodies - which are the names of the protein clumps which cause this disease when they accumulate in the brain; vascular dementia, which is where reduced blood flow to the brain causes the damage; and finally, the most common and well known cause of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, causing 60-80% of dementia cases globally.

Put simply, Alzheimer’s is where proteins negatively affect the brain's function by damaging the nerve cells. People can experience mild to severe memory loss as it worsens, as it usually starts to develop in a part of the brain known as the hippocampus, which controls aspects of our memory. The average life expectancy of someone suffering from Alzheimer’s is around ten years after diagnosis - and it is important to remember that the disease may have begun to develop up to two decades before there are recognisable symptoms that can be diagnosed.

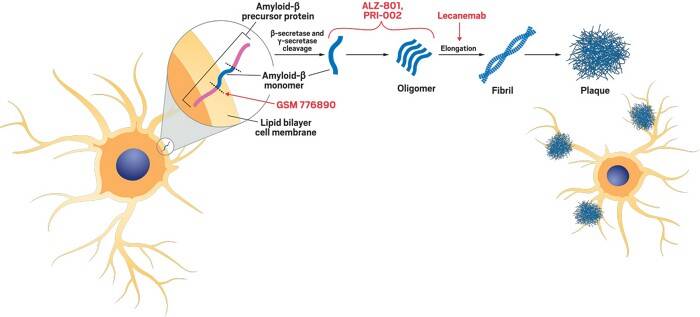

The two proteins which damage nerve cells in the brain are called Tau and Amyloid-beta. They are present in all of our bodies but, in someone living with Alzheimer’s disease, these proteins clump together and damage cells. The latter is caused by the breakdown of a large protein called amyloid-beta precursor protein, which is supposed to aid the growth and repair of nerve cells. With Alzheimer’s these proteins leave behind the amyloid-beta as by-products, which end up clumping together in between neurons as plaques. The spaces in between neurons are key in brain signalling, its where transmitting chemicals travel through, and so these protein clumps can cause severe interferences. Tau was recognised as a potential cause in the 1980s. This protein’s job is the reinforcement of neuron’s shapes, but if the protein is not the right shape, it can accumulate and form toxic clumps inside the neurons which can cause them to die.

Two potential treatments for Alzheimer’s recently explored are called donanemab and lecanemab. These cannot prevent the disease, or cure it, however, it can slow the decline of someone suffering from Alzheimer’s - and as the disease is mostly diagnosed when people reach their 60s, it can greatly improve their quality of life for the majority of it remaining. Both drugs utilise monoclonal antibodies, which are clones of an antibody designed to fit onto a specific shape found on specific cells.

See above: Diagram of how Lecanemab works to prevent the progression of plaque buildup.

See above: Donanemab, or Kisunla.

Donanemab, manufactured by a pharmaceutical company called Eli Lilly, is a disease modifying drug, and therefore it targets the causes rather than masking symptoms. It is administered intravenously in several doses and works by binding to the clumps of amyloid beta and making it more difficult for them to form more or larger clumps. Its side effects include relatively small issues such as nausea and headaches, yet also more serious risks such as brain swelling or bleeding. This is why it must be administered in a hospital setting at roughly month-long intervals. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MRHA) approved donanemab in October 2024. A high percentage of the people suffering from Alzheimer’s who have taken this drug show promising results, having experienced approximately no decline in their memory after one year, and the results overall show that decline can be reduced by several months.

Lecanemab was developed by the companies Eisai and Biogen, and it is another disease-modifying monoclonal antibody, which acts similarly, but is more preventative binding to the clumps of protein in the brain before the fibres have fully formed into a plaque. It is also administered intravenously and its side effects include vision changes, dizziness and confusion, and in some cases severe allergic reactions or brain swelling. This drug was approved in August 2024 by the MRHA for those who had been diagnosed with the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and there seems to have been successful results: in the testing stages, only 24% of those who had taken the drug continued to significantly decline.

Unfortunately, these drugs are very expensive to manufacture and administer to all who may need them, and so even though they are medically approved, they were rejected by the organisation NICE - the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence - for usage in the NHS. The costs of these treatments for the NHS’s resources outweigh the benefits they offer people. Despite this, donanemab and lecanemab show a lot of progress in research on this front have been made, and indicate a potentially more effective treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, and even other causes of dementia, could be made available sooner than we would have thought before.

Add comment

Comments