By Siha Hoque

Throughout our lives, many of us have heard the phrase, ‘Beauty is in the eye of the beholder,’ or that, ‘Beauty is subjective,’ in relation to who and what we as individuals find attractive, as something unappealing to you can be perceived as the ideal by another person. As well as this, it is not just people we may see as beautiful, but various forms of art, natural landscapes, many genres of music and something as simple as the arrangement of flowers - the list is endless, and the feelings we have in response to beauty are intricate. Beauty beyond survival and reproduction is in fact, as a concept, a very human experience. Our complex psychology allows us to feel pleasure from simply allowing our senses to experience things which, from a perspective completely devoid of the meaning we give it, are really just shapes, colours and textures. And to further indulge in that feeling we have actively created art, since prehistoric times, such as the handprints on cave walls, or the small sculptures formed out of rocks and wood. Yet, why do we feel this way about certain features in the world and what exactly determines which of these we enjoy and which ones we dislike?

The general chemical response to beauty is an influx of dopamine, the addictive ‘happy chemical’ in our bodies. However beauty is a spectrum; there are a variety of positive feelings we can have in response to something, each very different to one another, after all, we wouldn't feel the same about an expanse of sunlit mountains the way we would to a small baby animal. Firstly, looking at the concept of ‘cuteness’ - the response we have to it is something humans have developed for evolutionary purposes. The ability for our young to appear cute ensures we pay close attention to and take care of our babies, increasing their likelihood of surviving childhood. It is a surprisingly strong (and in fact quite manipulative) feeling, seeing as all of us are capable of feeling it from a young age, not just when we reach parenthood - and often how adorable we find an animal can overcome how dangerous it really is. Studies from the University of Oxford prove that we enjoy looking at cute things, and whether or not we are aware of it, we will often spend extra energy on prolonging how long we can see something cute. Other mammals such as gorillas and monkeys are very nurturing too, and it's very likely that they also find their young ‘cute’. The features regarded as endearing in numerous studies are based on those of babies and therefore include near disproportionately large eyes, a large head, softness and an overall small size - the fragility increases our compassionate urges and desire to provide protection. These are typically seen in most of the animals, teddies and cartoons which we may find sweet. The specific part of the brain being engaged by this response is called the orbitofrontal cortex, and it is a shelf of the brain above the eyes, linked to emotion and pleasure.

See above: Gorilla with its offspring.

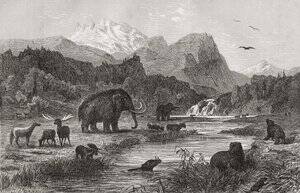

A completely different kind of beauty is that of a landscape; there probably isn't the same desire to protect and care for it, or to love it the same way as a partner, but it is rare for someone to say they would actively dislike looking at a photograph of some kind of aesthetically pleasing natural phenomena. This also in fact has some evolutionary roots: the landscapes we find beautiful resemble the landscapes from the pleistocene epoch where humans evolved - with a mixture of plains and hills, a large water source, other animals - particularly non predatory ones, clusters of trees which provide shelter and a sunny, warm-looking sky. Then what about the dangerous landscapes that we find beautiful? Snowy jagged mountain ranges and stormy cliff sides and bleak desert ranges? They aren't ideal for us to survive in, yet they can spark a strong sense of longing and awe. Some have theorised this is where our individual psychology has developed and overridden the anxiety an early human would have been wired to feel in response to an extreme environment. Knowing that we have what we need to survive available, and with safer travel to such dangerous places made possible, all that really remains is the enjoyable adrenaline from risk taking and the curiosity to gain more experiences. In fact many of us may simply want a change from the mundanities of our regular life, or be influenced by the desires of others. The skill it takes to abseil a mountain, a visit to a beach abroad being seen as impressive - these are all reasons why someone may find a certain type of landscape appealing - because of what it is associated with and what it represents.

See above: Sketch of the ideal Pleistocene landscape/habitat for humans.

What we as individuals find physically beautiful however is far more complex, but still more than you may think is down to evolution - we aren't just wired to find the physically fit good-luck; since prehistoric times early humans have found beauty in skill, and demonstrations of it: art. It has been theorised by some scientists that the earliest forms of art (mostly carving rocks) were present before speech, and those that were good at it were seen as more attractive, and more likely to reproduce. Throughout history, and even looking back on the past, we can appreciate an ancient sculpture or instrument because we can recognise the skill of the creator. What we have which early humans more likely did not, are stereotypes and preferences which are not purely focused on, and in fact often contradictory to our good health and therefore natural selection. A popular theory amongst scientists is that the form all living animals have in the present day is a balance between what features best fit their environment, and what features others of those species found attractive. Most of the time the two coincided - for example its likely the bigger and stronger would be more appealing to a mammal than the thinner and more feeble. However, and a famous example of this explored by Charles Darwin, who created this theory of sexual selection, is peacock tails.The plumage of the peacock has developed and became huge, however it is mostly a hindrance to the peacock itself. This is due to peahens finding them more desirable, and reproducing with birds that have larger plumage.

This certainly applies to humans as well, as of course our need to conform to a physical standard in order to survive is far lower, allowing what we find beautiful to be more extreme and less healthy. Biologically, we are ‘supposed’ to find traits and physical aspects that are familiar to us attractive, as they indicate safety and nurture. Psychologists from the University of Swansea theorise that this is something called sexual imprinting, where at a very young age people use those surrounding them to form an idea of what characteristics a biologically good partner would have. We are also designed, like all species, to find some physical characteristics which are different to our own appeal as well, likely to increase genetic variation and give us stronger chances of surviving disasters. Overall, biology only offers a base of sorts - it can explain instinctual preferences, but we are far more complex than that in the present day.

It is very well known that stereotypes play a key part in what we regard as beautiful, as we often believe looks can reveal what someone is like beneath the surface. This mindset develops at a young age through the media we engage with, as it has frequently presented protagonists and antagonists with physical appearances that correlate with their moral standing. For instance the heroines of a cartoon will often be slender, with softer and more delicate features; features associated with cuteness. The heroes are more likely to be broad, strong and tall, with sculpted features, particularly in comparison to the antagonists. On the other hand, the villains are older and less conventionally attractive, with exaggerated flaws, often overweight and unhygienic. These design choices are often not intended to be harmful, however, subconsciously, we start to build associations based off of the representation we are given, and so we could genuinely believe that beauty equates to morality. This is referred to as implicit personality theory, where we make assumptions based on appearances. Manifestations of this in real life could be children being more likely to trust a conventionally attractive adult compared to one who is not. It also means that we would be more inclined to treat someone who looks nice more kindly than someone who does not. What this means for a generation who was exposed to this kind of media from a young age and onwards is that when they grow up, they will feed into the beauty standard presented by the protagonists by pursuing people who they may subconsciously assume will have positive personalities - people who are stereotypically attractive. Furthermore, our own self perception plays a large factor in who we find attractive. For example, people state that they would want a partner who makes them feel taller or shorter by being the opposite; who we find beautiful is often influenced by if they make us feel it too.

However, it is important to remember that there is not a universal beauty standard. Different cultures have different historical and social factors which determine their present day beauty standard. What generally makes something the beauty standard, as seen through history, is appearing as the wealthy or upper class do - a good example of this is in ancient Greece where curvier women were seen as attractive as it showed they could afford to eat well, or in the Victorian era having pale translucent skin, because it implied you never worked outside. In the present day, there is a lot of work going towards body positivity, in order to make progress on reducing the both physically and mentally harmful goals people may be attempting to reach.

In conclusion, beauty can be found and expressed in many different forms of art and nature in the present day and likely from our beginnings as a species. The ability to draw pleasure from passively and actively indulging your senses in the surrounding natural world and art in its many forms is something that is partially unique to individuals based off of the environment they were raised in and partially a pleasant side effect of our evolution; and so are the ways in which we form ideals and decide which characteristics we find beautiful.

Add comment

Comments