By Siha Hoque

It is easy to assume that without connection to the rest of an organism's anatomy, brain cells do not possess any ‘inherent’ intelligence and therefore cannot ‘think’. However, scientists from UCL’s institute of Neurology and Australian biotechnology company Cortical Labs prove otherwise after creating DishBrain.

DishBrain is a system of lab-grown human and mouse brain cells, or neurons, which have been connected to a computer, and have since been taught to play the table-tennis video game Pong.

See above: Video game table-tennis, Pong.

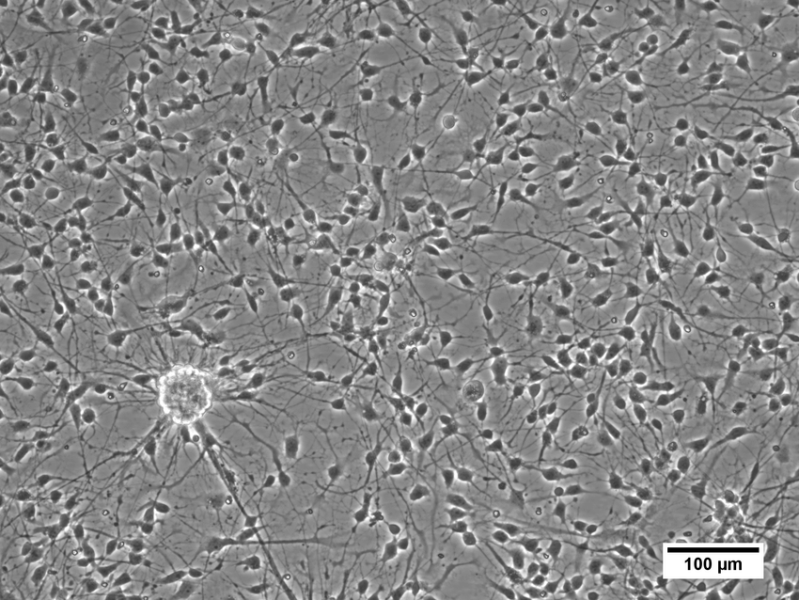

See above: Microscope image of cortical neurons.

Cortical Lab’s goal was to create a biological computer which could outperform the currently available electrical ones. The human brain is believed to be able to perform a quintillion operations in one second, using only 20 watts - one million times more efficient than the more advanced computer currently available.

In order to create DishBrain, scientists first harvested 800,000 cortical neurons from developing fetal mouse brains, as well as from human stem cells. Cortical neurons are nerve cells forming the cerebral cortex, and are broadly speaking responsible for information processing. This biological component, the ‘wetware’, was then allowed to grow on top of microelectrode arrays which would allow the electrical activity of these cells to be detected and monitored. This microelectrode array also provided the vital physical interface with the digital game, and stimulated the neurons with electrical input.

This arrangement allows the neurons to play pong by directly feeding them information. The left or right side of the array would stimulate a small portion of the neurons to indicate which side the ball was on, and the frequency of these stimulation would indicate how far the ball was from the paddle. This altogether enabled the cells of DishBrain to act as the paddle on the screen, and move to bounce the ball back. Whilst a lot of previous research has proven that neurons can be grown upon and have their electrical activity monitored by microelectrode arrays, DishBrain demonstrates a new level of interaction and capacity from the brain cells.

See above: DishBrain.

An interesting observation from DishBrain playing pong was how it began to learn and adapt to its situation. When the ball was missed, the electrodes would stimulate the neurons in random locations and at random frequencies - in other words, unpredictable behaviour. However, when hitting the ball successfully, the cells would receive a concentrated and ‘predictable’ signal in one location, a response which reinforces their actions.

The neurons aimed to reduce these random signals and maximise the predictable ones, supported by the Free Energy Principle, which can be summarised as a self-organising system maintaining its existence and resisting disorder by minimising prediction errors from its sensory inputs. Professor Karl Friston (UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology) who proposed the Free Energy Principle, states, “you cannot teach this kind of self-organisation; simply because – unlike a pet – these mini brains have no sense of reward and punishment.”

Nonscientific research has been very difficult to conduct until more recently, with the obvious ethical challenges of experimentation on living human brains leaving researchers to experiment on limited computational models and animal brains. Since DishBrain has become available, scientists can build living models of the human brain from its basic components instead, and rely on those for drug testing and experimental gene therapies, as well as provide insight to conditions such as epilepsy and dementia. In the near future, researchers plan to test the effects of alcohol on DishBrain, in order to see how brain cell performance in the game pong changes when inebriated.

Furthermore, DishBrain forms a key part of developing neural networks in artificial intelligence, as it currently proves to be more efficient at adaptation and learning than AI. Additionally, these biological components could be trained to control robotic limbs, allowing a more intuitive and adaptive real-world interaction from them in prosthetic, and represents a large step toward developing even more complicated bio-digital hybrid technology.

Add comment

Comments