By Siha Hoque

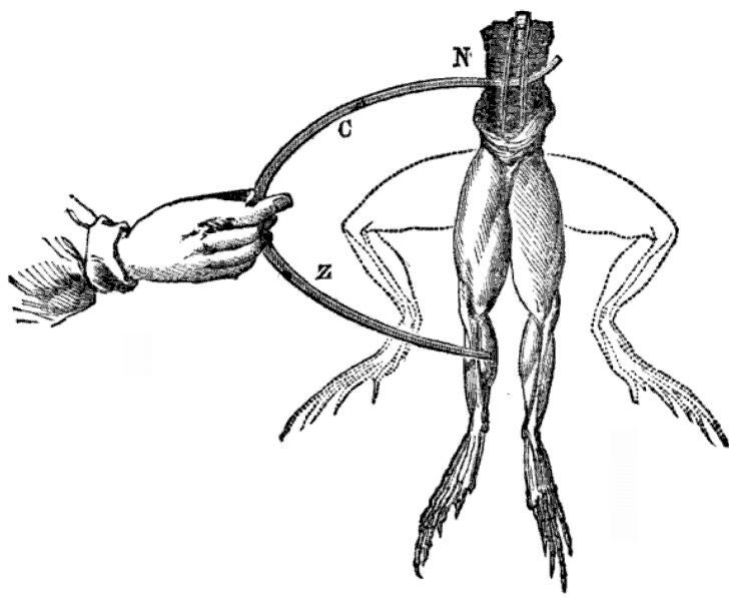

See above: Diagram of Galvani's Frog's Leg Experiment.

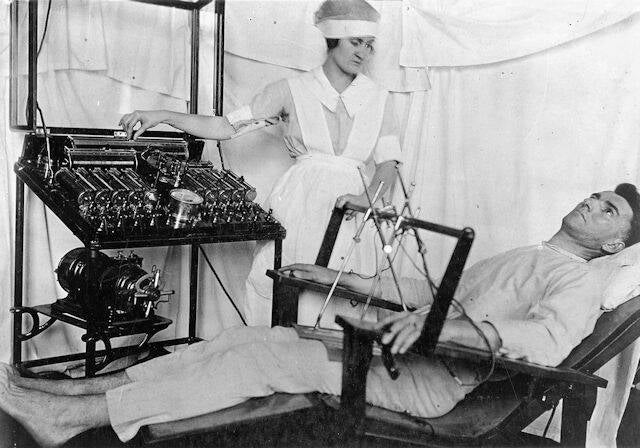

See above: Early 'electroshock therapy' used on shell-shocked WWI soldiers.

The ‘spark’ of electricity has been present in medical history even before its official discovery, and the subsequent incorporation of it as a valuable resource utilised in our day to day lives. Electrotherapy, as well as electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) is the direct use of electricity to treat injuries and illnesses. It has applications in the treatments for a variety of illnesses; from damaged muscle rehabilitation to extreme depression.

From the eighteenth century Italian physician and physicist, Luigi Galvani, we know that the human body’s nervous system is dependent on small amounts of electricity. The existence of which was proven by Galvani’s frog legs experiment, where he electrically stimulated severed frog legs, which remained connected to part of the spine and had exposed nerves. The spinal nerves were attached to brass hooks which caused the legs to spasm when a current passed through it. From this, Galvani theorised that the body naturally had an electrical fluid within it. Although not entirely correct, the idea of the body containing its own electricity was; and we generate this electricity by the movement of charged nutrient ions, the current of which travels down the length of/axon of a nerve cell. Between nerve cells are gaps known as synapses, and in order to cross this gap, the electrical signals are converted to chemical signals, before returning to electrical in the next cell. These tiny signals are responsible for our conscious and subconscious movements, from the natural beating of a heart to the arm movements required to climb a tree; our nervous system relies upon chemical and electrical changes to communicate across the body.

The discovery of this bio-electricity was shortly followed by adaptation of electricity to aid us when our natural supplies fail. A commonly known application of this is the use of defibrillators, where in the event of heart failure, or a deeply irregular rhythm, a shock can be delivered to momentarily stop the heart, and ideally allow it to return to a normal rhythm. The heart’s beating is dependent on a group of cells located in the upper right of it, known as pacemaker cells, which generate electric impulses that stimulate muscles to contract.

More recently discovered electrotherapies are present in physiotherapy, a field of medicine dedicated to mobility and function of the human body. Often, after surgery, atrophication, or injury, people are in need of muscle rehabilitation to restore the former abilities of specific body parts. Electrotherapy often features in the process, with treatments including electrical muscle stimulation (EMS), neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES, and functional electrical stimulation. All three of these treatments have the same effect - manually inducing the contraction of a muscle, whether it is through an electric shock to the surface of the skin or closer to nerves in the periphery of the targeted muscle. These forced contractions often ‘reawaken’ the muscle, and increase the regenerative ability of the stem cells surrounding muscles, known as satellite cells. This is why it is often used to generally speed up the process of healing wounds and injuries in the body. With electrotherapies such as those listed above, patients receiving this treatment can feel up to a 15% improvement in their muscle function in as little as 5-6 weeks.

Pain relief can also be provided by electrotherapy. Similarly to muscle rehabilitation, this kind of pain relief is often provided in the recovery after surgery, or for chronic pain. It is delivered through the same methods, but includes TENS - transcutaneous electrical nerves stimulation - and this overall reduces the signals of pain travel from affected nerves to the brain. Generally within this therapy, electrode pads on the surface of skin are used to deliver shocks to sensory nerves in the area. This releases endorphins, which are the body’s natural chemical painkiller. However, its main effect is based on the ‘Gate Control Theory’ of pain, which was proposed in 1965 by psychologist Ronald Melzack and neuroscientist Patrick Wall. This theory suggests a way to reduce pain or the detection of it is by preventing the sensation from reaching the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) by closing ‘the gate’ to them - after all, pain as a sensation is felt when special receptors in the body detect harmful stimuli and signal it to the brain. This is actioned by sending non-painful signals to specific large nerve fibres, and disrupting their connections to interfere with the pathway for pain signals to pass through. The effectiveness of TENS varies, and is better for immediate relief after injury, and for moderate pain only.

Aside from the physical relief and healing electrotherapy can provide, electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, has become more widely approved and used for the treatment of mental health disorders since the 2000s. Summarised, it is the use of electric shocks to restore the chemical balance and function of the brain by inducing small seizures. Often, mental illnesses can have physical/chemical roots or manifestations, meaning that they can be treated through these forms as well. The Royal College of Psychiatrists describes ECT to be ‘considered when other treatment options such as psychotherapy or medication have not been successful’ and due to the surrounding risks, this is a reasonably guarded treatment.

Disorders treated by ECT include depression - which is defined as a constant feeling of sadness, often causing a loss of interest in daily life- and more serious issues. Chemically, when depressed, the brain lacks in neurotransmitters known as serotonin and dopamine, which are chemicals responsible for feeling happy, and positive emotion in general. This is however, a gross oversimplification of the biology occurring. Depression is a serious matter and due to the intricacies of the brain and the various impulses within, two people who are considered clinically depressed may have completely different causes for this, which means that treatments often have to be tailored specifically.

The process of using electroconvulsive therapy to treat depression involves the patient being given a muscle relaxant and general anaesthesia, before electrodes are applied to the head. These deliver electrical pulses, and induce small seizures, sudden and disruptive neural activity in the brain. ECT is used to treat depression by targeting the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of the brain, areas which also typically respond to antidepressant drugs. In these areas, it increases the level of transmission between nerves, by stimulating the production of newer, more highly branched (and therefore more highly connected) brain cells. This allows more dopamine and serotonin to be transmitted across the brain, alleviating symptoms of depression. Unsurprisingly, there are many risks associated with ECT, including memory loss, confusion and nausea, but also more serious possible side effects, such as complications with heart rate and blood pressure due to the nature of the treatment involving the induction of seizures. Despite this, and likely due to the reservations of medical professionals when prescribing ECT, the results from this relatively new treatment appear to be positive - in 2019, 68% of patients claimed to have improved or nearly fully recovered from their depression.

The existence of electrotherapy, however, is far from new. Electricity became a resource long before its supposedly official discovery by Benjamin Franklin in 1752, dating even as far back as in Ancient Egyptian civilisations, electricity’s uses were present in early medicine, channeled through the resources found in nature. Electric catfish, found in the Nile, were stimulated to provide electric shocks for pain relief for gout, arthritis and headaches. This was, of course, dangerous, a large electric catfish could produce 450 volts of electricity, so likely only smaller fishes were used for this purpose. Similar to electrotherapy in physiotherapy in the modern day, it was possible that cell regeneration stimulated by the shocks did actually benefit those suffering at the time. Similarly, in Ancient Greece, a hotbed for the then developing practice of medical science, torpedo sting rays were likely taken advantage of to provide numbness through their electric shocks, allowing pain relief.

In the early twentieth century, the idea of psychology and a mind or ‘psyche’ was becoming a popular idea amongst many scientists of the time, their theories of a subconscious which can affect our behaviour often causing controversy. Amongst these scientists was Sigmund Freud, whose theories regarding ‘war neuroses’ or shell-shock, became explored in more depth after World War I, where a need for psychotherapy emerged. The effects of the terrible PTSD many soldiers suffered from, as a result of their time on the battlefield often resulted in a drastic change in the events and quality of their day to day lives. This often manifested as a range of symptoms, such as becoming mute, developing severe phobias, and hysteria. One of the methods attempted by many medical professionals to aid the trauma of soldiers so that they could return to the frontlines was electroshock therapy. This was a very crude, and often extremely poorly delivered treatment, which sparked a lot of the controversy that still surrounds views of electrotherapy today. The treatment itself would entail the patient being strapped down, and then having electrodes placed within their mouth, before a series of shocks would be delivered to them. Without any pain medication, this would be an extremely painful treatment, and often traumatic in itself. It was developed by 1927 Nobel Prize winner physician Edgar Adrian and Dr Lewis Yealland. The two believed that the pain caused by electroshock therapy would prove both therapeutic and disciplinary for soldiers, as shell-shock was unfortunately regarded by some as a weakness in soldiers. It is extremely unlikely for this treatment to have been beneficial for its patients.

Electroshock therapy in WWI is often why even modern day faradic treatments are so strongly scrutinised, particularly ECT. Some believe that, like in the 1930s, ECT is a form of medical abuse, used to control vulnerable patients, and that no one in a position to give informed consent to such a treatment would actually do so. Others disagree with the concept of ECT as it essentially uses seizures, which are simply put, dangerous and deteriorative, to induce a recovery. Their argument is that this damage during treatment cannot justify the ultimate purpose of it. However, chemotherapy, which is used to treat cancer often results in a lot of damage to the human body as a whole in its efforts to eradicate cancer cells, and many would argue that it is a necessary sacrifice to be made in the pursuit of a longer life and highly improved quality of living. Although the diseases are not comparable, treating depression with ECT can, for nearly 70% of people, increase their quality of life and, therefore, their lifespans too.

Many professionals firmly believe that electrotherapy and ECT are ethical methods of treatment. Within medicine, ethics are primarily decided by whether or not a prescription or action meets the four pillars of medical ethics, which are beneficence (to do good), nonmaleficence (to not do harm), autonomy (right of the patient to decide upon treatment) and justice (equal opportunity). It could be argued that, through the thorough vetting process, not only the risk of ECT being a form of medical abuse reduces, but patients are ensured autonomy; beneficence, by improving the quality of life for those undergoing either physiotherapy or ECT; and therefore nonmaleficence - by having an ultimately effective treatment.

Overall, the quality of life for many has been improved by the existence of electrotherapy and ECT, not just in modern medicine but thanks to the journey and development of the treatment throughout history. It is still being researched by many scientists, both to see if the usage of electricity can be avoided, and if it can be adapted to do more. Either way, as the future of medicine and many treatments becomes less and less invasive, the use of electricity in treatments may well be likely to increase.

Add comment

Comments