By Siha Hoque

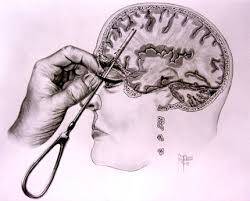

See above: Diagram of a transorbital lobotomy.

See above: Rosemary Kennedy.

Medicine is a field of science that is constantly developing, and has undergone many changes over the past century - in 1927, a machine called ‘the iron lung’ was invented by Philip Drinker to help patients paralysed by polio to breathe; researchers at McLean hospital discovered a new neural protein - brain proteolipids - in 1951; non-invasive foetal heart monitoring was developed in 1973; and in 2022, the process of a viral infection was caught on camera. These are all successful discoveries, however in some cases, supposedly revolutionary medical practices were in fact incredibly damaging and did provide the care doctors hoped they might. In 1949, Portuguese physician Doctor Antonio Moniz received the Nobel Prize in Physiology for developing the lobotomy. Lobotomies were a brief yet definitive era in the development of psychiatric care, considered to be a breakthrough in treating mental illness in the early twentieth century, and now viewed as an unethical and barbaric practice.

The lobotomy was developed in 1935 in the Hospital Santa Marta in Portugal. Its aim was to treat or relieve the symptoms of mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and manic depression. A lobotomy would do this by severing the nerve fibres from a part of the brain known as the frontal lobe from the thalamus, and there were several methods for this. The frontal lobe is key for executive functions such as reasoning and problem solving, as well as controlling voluntary movements and both interpreting emotions and expressing them through behaviour. The thalamus is used to process information sent in from the majority of your senses before sending them off to be interpreted by the cortex of the brain.

The two most common procedures used for a lobotomy were the transorbital and prefrontal. The prefrontal lobotomy consisted of drilling two holes into the patients head to access their brain, before using a tool developed by Moniz known as a leukotome (designed to sever and disrupt nerve fibres) to cut between the frontal lobe and thalamus. This would damage what doctors believed to be the neural tracts responsible for the thought patterns in mentally ill patients. The transorbital lobotomy was developed by American physician Walter Freeman in 1936, and he wished to simplify Moniz’s lobotomy procedure so that they could be done by psychiatrists across the world. In a transorbital lobotomy, a sharp, ice-pick-like instrument known as an ‘orbitoclast’ - originally an actual icepick - would be inserted under the eyelid and placed against the eye socket. It would be driven in through the thin bone and into the brain, where the surgeon would manoeuvre it at specific angles and depths (described as similar to the motions of a windshield wiper) to sever the connective tissues between the frontal cortex and thalamus, before returning it to its entry position and withdrawing it. This would then be repeated on the other side.

Around 50,000 people in America alone received lobotomies, and unsurprisingly, the lobotomy caused some patients severe brain damage, and killed others. The intended result was to reduce the agitation observed in schizophrenic and depressed patients - to bring a sense of calm. Patients displayed lower levels of tension, making the lobotomy appear successful in the early days. However, most patients began to display other symptoms as well, such as being apathetic and passive in life. Patients’ personalities changed, becoming more withdrawn. They responded with a lower depth of emotion to stimuli and often struggled with focus - all almost certainly caused by the damage to their frontal lobe and thalamus. The lobotomy had become popular by 1940, despite the mixed results displayed in the first 40 patients to have undergone this surgery. It was recognised initially as an extreme procedure yet there were very few other options available for patients who were violent or self destructive due to mental illness. In the early twentieth century, mental asylums were overcrowded, and patients would be separated from their families to be kept there for their own safety and care. Lobotomies had the potential to help patients return to a mental state where it would be safe for them to return to their families, and therefore eventually resolve the issue of overcrowding.

Neurosurgery used to treat mental illness was first used by Swiss psychiatrist Gottlieb Burckhardt in the late 1800s, who removed parts of the brain from six schizophrenic patients. They were not known to be schizophrenic at the time, however carers recognised that they experienced hallucinations and other symptoms associated with it. He saw that his operations resulted in them becoming quieter and theorised that although this surgery would certainly not restore a sick person’s sanity, it would be a last resort to allow a patient to be calmer and peaceful for the rest of their lives. Burkhardt’s ideas were linked to the experiments of Freidricht Golt, who performed similar operations on dogs where he removed small amounts of brain tissue from them, and later noticed changes in their behaviour afterwards.

Antonio Moniz was born in November 1874, and he studied medicine at the University of Coimbra, before graduating in 1899. He led a political career from 1900 when he was elected to parliament, becoming Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1917, to when he retired in 1919. At the age of 51, Moniz returned to medicine full-time and conducted a series of experiments, after which he successfully theorised the brain using substances that were not visible with X ray radiation. When developing the lobotomy, or what he had called the ‘leucotomy’, Moniz had theorised that mental illness was caused by strange neural connections within the frontal lobes. He had also observed behavioural changes in the behaviour of soldiers who suffered injuries to their frontal lobes. Due to having gout, Moniz was not able to operate himself and so he had neurosurgeon Pedro Lima perform lobotomies for him, first on 20 patients. The results produced were mixed, only seven of which were considered to be ‘cures’, but when this gained popularity the lobotomy was seen as hope for those suffering from mental illness - at least until the 1970s.

The first lobotomy Freeman performed was apparently successful. Alice Hood Hammatt suffered from severe anxiety and depression, and was 63 at the time of the surgery. She was operated on by Walter Freeman, and after the surgery expressed a disinterest in her past fears and their causes. For instance, prior to the operation the thought of having her hair cut short upset Hammatt, yet afterwards, when asked about it, she did not care at all. Hammatt also did not panic when her husband visited or left her hospital room, though previously it would have done so. A few days after surgery during her recovery she exhibited symptoms that appeared contradictory to the surgery’s success, including excited stammering, however as swelling in her brain went down, she returned to her previous post-lobotomy state. After she left the hospital, Hammatt claimed she experiences less anxiety in her day to day life, and she was able to live at home for the rest of her life without the care of a nurse or some of the medication she took previously.

A famous example of a lobotomy which failed was performed on Rose Marie Kennedy, in 1941. As a young adult, she had often exhibited violent outbursts and conclusions, and at the age of 23 doctors recommended the surgery to her father, saying it could cure her aggressive behaviour, and he agreed to it. In reality it was likely that she had had a form of depression, however due to general denial of such mental illnesses and to protect their reputation, her condition was referred to as being mentally impaired. In November of 1941, Walter Freeman and neurosurgeon James Watts operated on her. She was given tranquilisers yet awake during the surgery to determine the depths of the incisions, and while the surgeons worked she was told to recite the Lord’s Prayer or sing, or count. They stopped cutting through tissue only when her words became incoherent. Almost immediately after the surgery it became very clear that it completely failed. Kennedy lost control over key bodily functions; unable to walk by herself, communicate normally or control her bladder, and her mental capacity was reduced to that of a young child. As soon as she was discharged from the hospital she was institutionalised.

Another famous and unjust lobotomy was performed on an unsuspecting 12 year old boy, Howard Dully - who went on to write a memoir called ‘My Lobotomy’. He was unruly, in similar ways to many other children his age, yet was labelled with ‘psychological problems’ by his father and stepmother who allowed Freeman to perform a lobotomy on him, despite several psychiatrists telling them that Dully had nothing wrong with him. He had a transorbital lobotomy, and he is not aware of any of the effects it may have had on him, stating in his book, “I’ll never know what I lost in those 10 minutes, with Dr Freeman and his ice pick.”. The surgery did not cause him noticeable mental damage or affect his physical abilities, though the recovery was incredibly painful. Dully was forced to leave his family home not many years after the surgery, and spent years in juvenile centres and mental hospitals. He eventually recovered from bad habits he had developed over those years, such as drug usage and heavy drinking, and he is now a tour bus driver living in California with his wife and two children.

Not all patients who had lobotomies had actually been mentally ill. Various forms of discrimination played a key part in who was deemed necessary for this surgery. Over two thirds of lobotomies performed were on women. Women and people of colour would have been given far less leeway than others when it came to what was within the range of normal behaviour and the behaviour of someone who was uncontrollable. Women would be rendered passive and near apathetic after the surgery, and as this roughly complied with the ideal stereotype, it was seen as some form of ‘treatment’ for normal, yet disliked, behaviour. Additionally, some had the wrong belief that lobotomies could ‘cure’ homosexuality, furthering the misuse of an already crude surgery. Approximately 40% of Freeman’s patients were gay men who were given this operation to change their sexuality.

Overall, lobotomies are a crude and terribly misused form of surgery, once seen as a way of offering those who were mentally ill a new life. It has unpredictable results, with unethical ‘positive’ ones that alter one’s emotional and mental capacity, and seriously debilitating negative ones that range from severe brain damage to death.

Today, in the UK, neurosurgery for mental disorders can no longer be performed without the patient's consent. The last known lobotomy performed in America was in 1967, (resulting in the patient’s death) although it is still legal there and in some parts of Europe. Occasionally today, psychosurgeries similar to the lobotomy are performed, where parts of the brain tissue are removed, though in incredibly rare and necessary cases, with far more precision and accuracy.

The use of lobotomies decreased in the mid 1950s, when a far more reliable alternative was discovered: antipsychotics and antidepressant drugs. These were far more effective and posed a significantly smaller risk than the messy surgery. The media also began to criticise the operation, such as in the 1958 film, ‘Suddenly, Last Summer’ where a lobotomy is depicted being used to render an innocent woman withholding a secret to be unreliable, so that she would no longer be trusted by society - regardless of the surgery’s outcome. People recognised that as well as the potential misuses, there was not much research on or positive outcome from this surgery, and so they started to view it as a barbaric procedure, and turned away from it in the 1960s, allowing this era of medicine to reach an end.

Add comment

Comments